Question More, Action Knowledge.

Remember, at QMAK, we don’t just teach; we empower. We don’t just inform; we inspire. We don’t just question; we act. Become a Gold Member, and let’s unlock your child’s full potential, one question at a time.

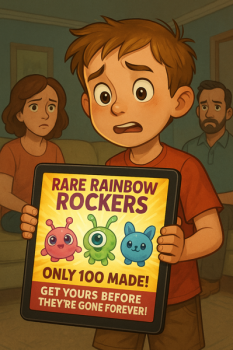

Oliver stared at the colorful advertisement on his tablet. “NEW! RARE RAINBOW ROCKERS – ONLY 100 MADE! GET YOURS BEFORE THEY’RE GONE FOREVER!”

The digital pet toys looked amazing – small, colorful creatures that could sing, dance, and interact with each other. The commercial showed children playing with them, looking absolutely delighted.

“Mom! Dad! I need Rainbow Rockers!” Oliver called out, running to find his parents. “They’re super rare and everyone at school will want one, but they only made a hundred of them!”

Dad looked up from his book. “That sounds interesting. Why do you want one so badly?”

“Because…” Oliver paused, thinking. “Because they’re rare! And they might sell out any minute!”

Mom and Dad exchanged knowing glances.

“Oliver,” Mom said gently, “it sounds like you might be experiencing something called scarcity bias.”

“What’s that?” Oliver asked, still clutching his tablet with the Rainbow Rockers advertisement flashing across the screen.

“It’s when we want something more just because it seems hard to get,” Dad explained. “Our brains are wired to pay special attention to things that are rare or limited.”

“Like how dinosaur fossils are valuable because there aren’t many of them?” Oliver asked.

“That’s a good example,” Mom nodded. “But companies also know about scarcity bias, and sometimes they create fake scarcity to make us want their products more.”

Oliver looked confused. “Fake scarcity?”

“They might say ‘limited edition’ or ‘only a few left’ even when that’s not completely true,” Dad explained. “It makes us feel like we need to buy right away without thinking.”

Oliver looked back at his tablet. The advertisement now showed a countdown timer: “ONLY 24 HOURS LEFT TO ORDER!”

“I think I get it,” Oliver said slowly. “They want me to feel like I’ll miss out if I don’t buy it right now.”

“Exactly,” Mom said. “So before you decide about the Rainbow Rockers, let’s ask some important questions. Would you still want one if they weren’t rare?”

Oliver thought about it. “I’m not sure. The commercial doesn’t really show what they do besides light up and make sounds.”

“Good observation,” Dad said. “And here’s another question: do you know anyone who already has one? Do they enjoy playing with it?”

“No,” Oliver admitted. “They just came out today. The ad says they’re ‘the hottest new thing.'”

Mom smiled. “It might be worth waiting a little while to see reviews or to learn more about them. Sometimes the ‘hottest new thing’ isn’t actually that fun after the excitement wears off.”

The next day at school, Oliver noticed several classmates talking excitedly about Rainbow Rockers.

“My parents ordered one right away!” said Lily. “They’re so rare!”

“I got the last one at the store!” Lucas claimed. “The salesperson said they might never make them again!”

Oliver felt a twinge of worry. Maybe his parents were wrong. What if he really did miss out on something amazing?

After school, Dad took Oliver to the toy store “just to look.” To Oliver’s surprise, there was an entire shelf of Rainbow Rockers, at least thirty of them, in all different colors.

“I thought there were only 100 in the world,” Oliver said, confused.

The store clerk overheard him. “Oh, that was just the special ‘diamond edition’ that was limited. These regular ones—we have plenty.”

On the way home, Oliver was thoughtful. “The ad made it seem like all Rainbow Rockers were rare, not just the diamond ones.”

“That’s how scarcity marketing often works,” Dad explained. “It creates urgency so you’ll buy quickly without researching or thinking too much.”

The following week, Oliver noticed something interesting. Many of the kids who had rushed to get Rainbow Rockers were already losing interest in them.

“The batteries only last like two hours,” complained Lucas.

“Mine keeps making the same three sounds over and over,” Lily sighed.

Meanwhile, Oliver had saved his allowance and researched other toys. He eventually chose a buildable robot kit that wasn’t marketed as “rare” or “limited edition,” but had hundreds of positive reviews from kids who had enjoyed it for months.

When his robot could finally walk across the room following commands Oliver had programmed himself, he felt a sense of accomplishment that no impulse purchase could have given him.

“You know,” Oliver told his parents one evening, “I’m actually glad I didn’t get the Rainbow Rockers. My robot isn’t rare, but it’s special to me because I built it myself and I learn something new about it every day.”

Mom smiled. “That’s the funny thing about scarcity bias. Sometimes we’re so busy chasing what’s hard to get that we miss the value in what’s already available.”

“Like how we get excited about fancy restaurants with month-long waiting lists,” Dad added, “when sometimes the best food is at the local place where anyone can walk in.”

From that day on, whenever Oliver saw advertisements claiming something was “limited edition” or “almost sold out,” he remembered the Rainbow Rockers and asked himself:

“Do I want this because it’s truly valuable to me, or just because it seems scarce?”

It wasn’t always easy to resist the pull of scarcity, but asking that question helped Oliver make choices based on what truly mattered to him—not just what was hard to get.

The positive messages include:

The elementary reading level is maintained through simple dialogue, concrete examples, and the relatable scenario of toy marketing, making the concept of scarcity bias accessible and engaging for young readers.

Remember, at QMAK, we don’t just teach; we empower. We don’t just inform; we inspire. We don’t just question; we act. Become a Gold Member, and let’s unlock your child’s full potential, one question at a time.